For a long time, research into the Holocaust focused on the groups of perpetrators and victims. Little attention was paid to the role of the ‘bystanders’, of the supposedly uninvolved majority population. In order to close this gap, a team of contemporary historians is researching the multitude of bystander perspectives – the nuances – using an international collection of diaries as ego documents. The project is led by Bielefeld professor Dr Christina Morina. Researchers from Bielefeld University and the Jagiellonian University in Krakow are collaborating on the project. In this interview, Christina Morina talks about her project group’s research.

Holocaust research has long focused on perpetrators and victims. Which opportunities does the term bystanding offer?

The term focuses on the so-called majority society – in other words, those contemporaries who cannot be clearly categorised as either perpetrators or victims. Bystanding describes the diverse positions and behaviours that influenced the violence and the specific and changeable roles that people took on in National Socialist society. However, the concept of bystanding helps us to explore society as a larger social structure which allowed mass violence, genocide and mass persecution to emerge and consolidate. In English, we try to move away from ‘the bystander’ as a fixed category or certain type of person, but rather speak of bystanding as a process, which enables us to study the Holocaust as a very complex and volatile history of manifold relationships between Jewish and non-Jewish people. This helps us to analyse how violent politics could become a social reality, and these efforts are very much in line with recent trends in Holocaust research. Scholars increasingly consider this monstrous event as a social process – not just as a political or military act, but as a social and even interpersonal phenomenon.

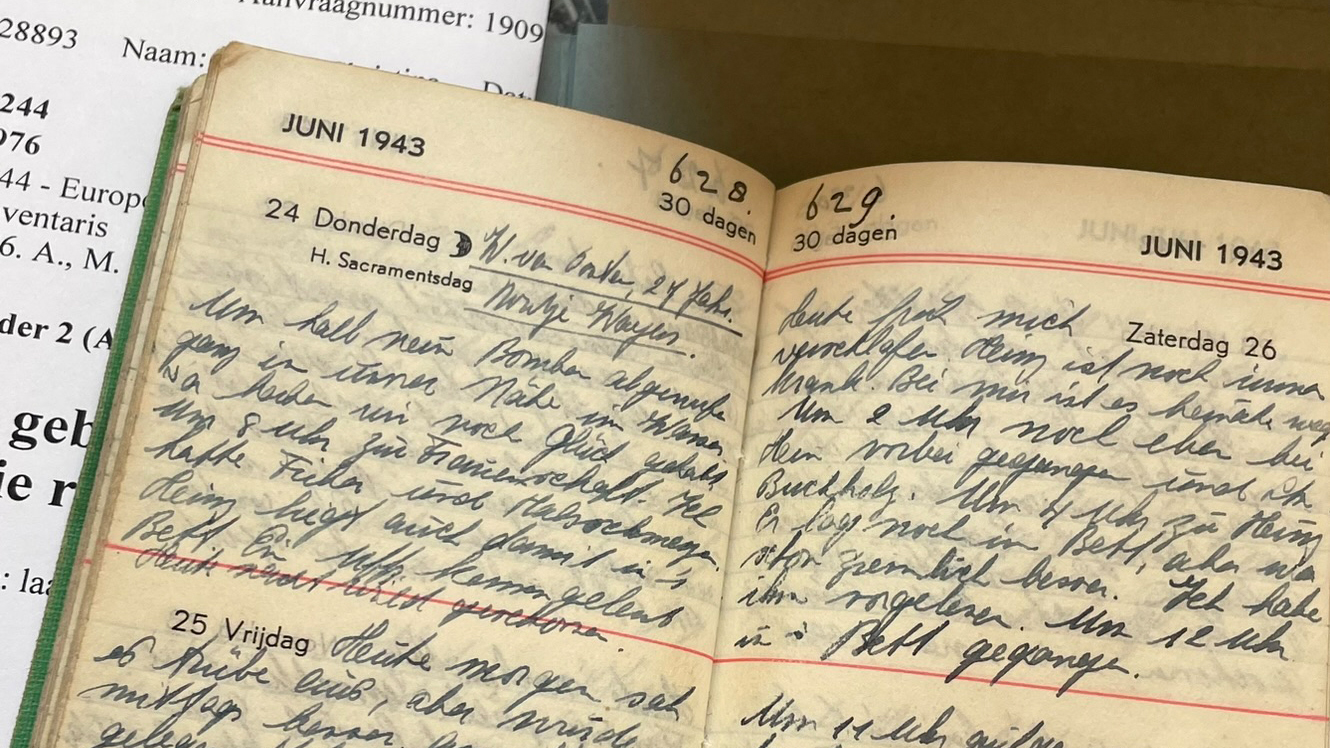

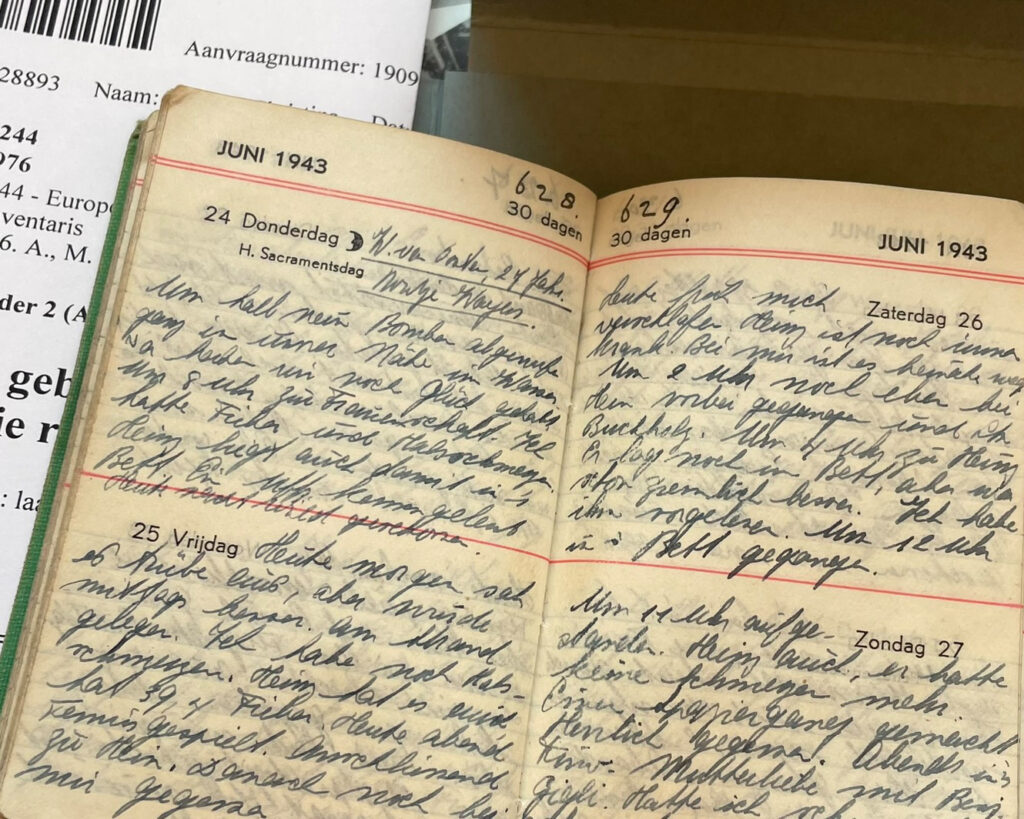

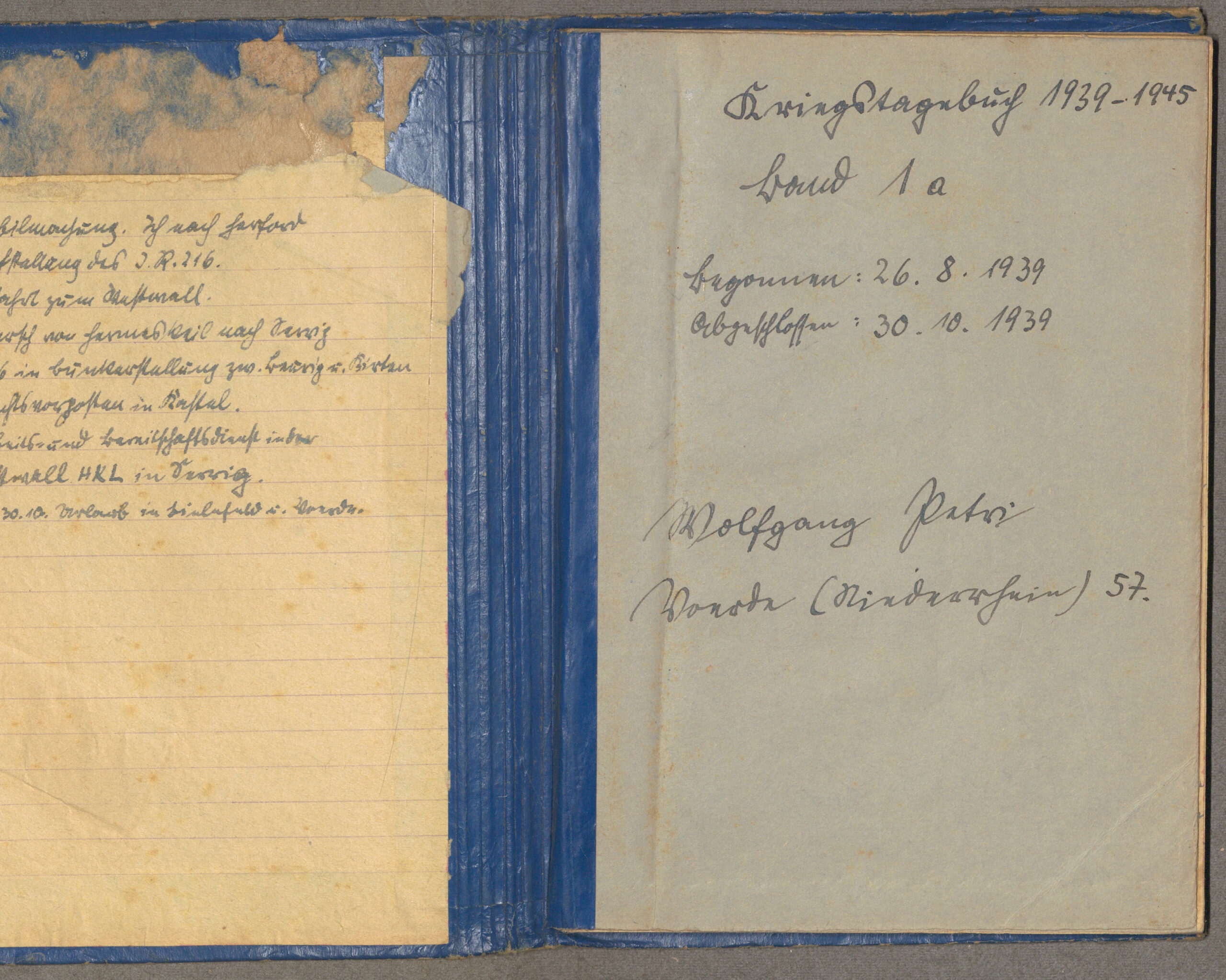

Your sources are ego documents, personal statements from the general public across Europe. You focus particularly on researching diaries. What is special about them?

Diaries are deeply subjective testimonies of individual reflections on the self, the world and the self in the world, so they are not only sources for perceptions of the self but also social sources, they reflect the environment, the life-worlds and fellow-human-beings surrounding their authors. People often turn to writing a diary to cope psychologically with stressful experiences. Victims’ diaries in particular therefore often report directly on and about violence. And people who were not directly affected by persecution also reflected in their diaries on the violence that took place.

Studying these documents enables us to understand how systemic violence developed and how it affected peoples’ and community lives – both on a social level and in direct relationships between contemporaries. Diaries depict larger cultural and social contexts as well as how people meet, interact and think about each other. That is why we can approach them with many different questions.

The project is made up of various sub-projects. What questions do they have in common?

A core question is the presence of antisemitism – both as a concept and term in the documents themselves and as a historical phenomenon with real causes and consequences. The term originates in the 19th century, it was invented by those who hated Jews as a self-description, and at the same time antisemitism is one central analytical focus of our research. We are therefore particularly interested not only in the diaries of victims, but also of ‘ordinary’ people, that is non-Jewish contemporaries who held neither a formal office nor bore a direct responsibility for the events happening at the time. How is the then-present antisemitic reflected in diaries in different contexts? What role do notions of community, nation and belonging play? How do self-images as members of the ‘folk community’ (Volksgemeinschaft) and citizens manifest themselves in Nazi Germany and the occupied societies in which the state was dramatically curtailed if not completely destroyed? And finally: How do those subjected to targeted persecution perceive the actions and attitudes of non-Jews?

In your sub-project, you are analysing how the existence during the persecution and murder of Jews is reflected in Jewish and non-Jewish diaries from Germany and the Netherlands. Can you already give some interim results?

In my project, I am comparing German society in the 1930s and 1940s with Dutch society. I systematically explore these questions for the first time on the basis of Jewish and non-Jewish diaries. The Netherlands had its own National Socialist movement in the 1920s and it experienced one of the highest death rates of Jews killed during the German occupation. I believe that the way in which Dutch people saw themselves as members of a nation and a state – and how they behaved towards their Jewish fellow citizens – was determined by how they saw their own roles in this society, what responsibilities they felt they had and what values and authorities they accepted.

National Socialist society in Germany, on the other hand, was heavily influenced by racist notions of superiority and socially widely accepted, state-propagated ideas of community, of a fatefully deprived nation of ‘Volksgenossen’ that was now revived or restored through Hitler’s rule. This was not just a propaganda formula, but a very attractive and effective political program captivating a large portion of society. The question of how to position oneself vis-à-vis Jews was central to this program because it was the central question for the regime – which was all about fighting an alleged ‘Jewish world conspiracy’. This is reflected in a number of diaries that I have analysed so far, albeit often subdued or implicitly rather than in overtly antisemitic diatribes, which requires particular methodological care. The fundamental systemic difference between both countries is that National Socialism became a government program and thus state policy in Germany. Its rise had a huge social basis, whereas in the Netherlands it was a minority movement against which democratic forces fought back relatively successfully in the 1930s and that was only able to regain influence with the beginning of the German occupation in 1940.

©

A comparison of the diaries thus shows major differences in the perception of Jews and non-Jews before 1940 but, at the same time, antisemitic and anti-Jewish attitudes were widely present in both societies, stemming from a centuries-old European tradition. This tradition had a decisive influence on what people considered as right and wrong, who they believe belongs and who does not, or who they deem and do not deem deserving of the protection of the state. Both societies responded partly along comparable Jewish/non-Jewish lines, in sync, again, with shared, deep-seated notions of a Christian-Jewish divide. But there were also stark differences because the dominant collective historical horizons of experience as well as popular understandings of state and statehood differed greatly – and thus also the respective ideas of citizenship.

But this is very much a work in progress, not least with regard to locating and collecting the source material. My team and I are currently searching for diaries from and from around Bielefeld. Our goal is to build up a comprehensive collection of at least 50 Jewish and 50 non-Jewish diaries from eight countries – Germany, the Netherlands, Austria, Italy, Poland, France, Switzerland, the United Kingdom and the USA.

Let’s switch to the present. You are currently a visiting professor at The New School in New York. How do you perceive the current discourse on German memory culture from a distance – especially with regard to the concept of bystanding?

The debate about how to deal with the Nazi past is currently incredibly polarised. My project aims to research the history of National Socialism from a societal and political-cultural perspective as well as its aftermath. It took decades after the war before scholars began to systematically examine the social foundations of National Socialism and the cultural as well as material conditions of its considerable appeal. In the wider public, this broad understanding has arrived even later and is still not as deeply anchored in popular perceptions of Nazi history as it deserves – in spite of immense efforts at historical-political education. Phenomena such as racism and antisemitism in present-day society should not be considered ‘recurrent’, because they are and have been ‘current’ for a long time. They reflect certain historical continuities, such as a still strongly ethnic-culturally tainted idea of what means to be (a) German, which has been and can again become the breeding ground for nationalism, discrimination and systemic, state-sponsored violence. Such notions of ‘Germanness’ have not yet been sufficiently deconstructed and problematised in politics and society.

How does this tie in with our research on bystanding? We aim to show how ideas of the self, of communal belonging and the state are formed and negotiated in a particular time and place and what consequences they have in terms of individual, societal and political-institutional behaviour. In this way, we want to add to our historical knowledge and provide fresh impulses for public history and historical-political education contexts. All to often, systemic violence is presented in such contexts as the result of political and military states of emergency – which it is, of course – but it is more than that. If we understand that systemic violence is always a social possibility, that it needs society, every-day people, to approve, however tacitly, and get involved, however tentatively, to strip entire groups of people of their rights and their place within society, we believe that we will be able to counter its resurfacing more effectively and in all its manifestations, from language to physical assault.

To what extent can your Bystanding project transcend the realm of historical-political education?

For a long time, the conventional wisdom has been that if we only educated people enough about the Nazis and the Holocaust, racism and antisemitism would eventually cease to be a problem. I believe this premise has quite obviously turned out to be misguided. Even with comprehensive educational programs about Nazism and its crimes established over decades, such knowledge does not suffice to banish racism and antisemitism from our society. How these two matters are actually interrelated is an important question; it should itself be the subject of interdisciplinary research. For me, addressing these issues to achieve a more effective – in the broadest sense – societal knowledge of Nazism is one of the most challenging tasks facing scholars of the Holocaust and its aftermath today. With the Balzan Bystanding team-project, we aspire to substantially contribute to this challenge.