The 27 countries of the European Union have now jointly adopted eight sanctions packages against Russia—even though the path to unity has not always been easy. The EU stands united against the Russian invasion of Ukraine. Dr Andreas Vasilache is professor of European Studies at Bielefeld University and German director of the Centre for German and European Studies. He explains why the European Union emerges stronger from crises in particular—and why Europe cannot rely on strong US military engagement in the long term.

How has the EU’s role as a peace project changed since the start of the Ukraine war?

As a peace project, the European Union has also always been designed to contain potentially unpeaceful actors. The French interest at the beginning of integration also lay in containing Germany, for example. That’s something we easily forget. Furthermore, outwardly, European integration was also the building of a community against a threatening hegemonic power, namely the Soviet Union. So, to some extent, the EU is now returning to this function. By contrast, in recent years and decades, the impression might have been that the European Union was more of an economic project than a peace project.

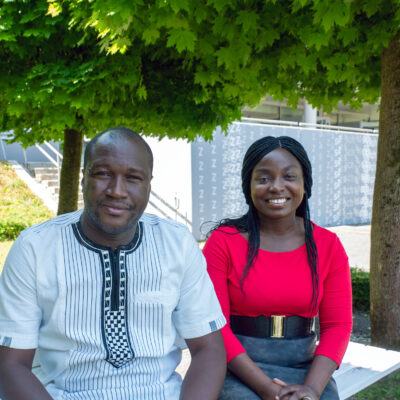

© Bielefeld University/M.-D. Müller

Will Europe emerge stronger from the tensions surrounding the Ukraine war?

The unity of the EU is surprisingly strong, despite differing interests and voices. We have seen that severe crises within Europe have often led to more institutionalized integration—even if things initially appeared to be different. For example, the financial market, banking, and sovereign debt crisis saw the introduction of new instruments and institutions. And the impression at the time that the crisis would lead to Europe falling apart did not prove to be true. During the Covid crisis, European integration deepened again thanks to the joint emergency fund and the joint purchase of vaccines. So far, the EU has responded to crises and disintegration tendencies with deeper integration. Whether this will also be the case during the Ukraine war remains to be seen. But its strong unity is encouraging.

Nevertheless, there are different positions within the EU.

Yes, but I do not see any serious conflict of objectives. What we are seeing in some cases are different perceptions of threat. When it comes to the Baltic states, the threat is, understandably, different to that for Spain or Portugal. The UK and France have nuclear deterrents, other EU countries do not. These differences can lead to different courses of action. But Europe is in agreement that the Russian invasion must be repelled and that a heavy price will have to be paid for this. This has been the consensus at government level so far. The extent to which this will remain the consensus in the different societies is difficult to gauge. In Germany, for example, there is currently support for the existing level of arms deliveries to Ukraine, but no majority for increasing them further. If the conflict continues, there will likely be consequences for governments.

© Bielefeld University/M.-D. Müller

What is the role of the United States in the joint fight against the invasion of Ukraine?

The United States is by far the biggest supporter of Ukraine, also in terms of weapons procurement. And simply because of the US security guarantees within the framework of NATO, EU countries see the United States as an important leading power. At the same time, this is a risky game in the long run, because in US society, the Russian invasion, while an important issue, is not as mainstream as we would like. Coming off two decades of intense military engagement, the United States is more concerned with itself. There is a certain war-weariness, and the polarization within society has reached unimaginable proportions. After the Republicans’ wins in the midterms—even if they were not as sizeable as anticipated—we can expect an even greater focus on domestic politics in the United States. Parts of the Republican Party embrace an equally isolationist and pro-Russian authoritarianism. US demographics are also changing. In recent years, only part of the influx of immigrants to the United States has come from Europe, but more has come from other parts of the world. Solidarity with Europe is diminishing.

So, will Europe need a rethink in the future?

US interest in Europe, which was taken for granted until the 1990s, is waning. Thanks to US security guarantees, Europe was able to prioritize positive social and economic development over military spending for a number of decades. European politicians were able to rely on the US commitment to shouldering these costs for Europe. It is very difficult to get out of such a situation. Germany is not the only country in which discussions about increases in military spending or even about nuclear armament do not win elections. Russia’s invasion of Ukraine could now lead to a rethink. There is talk about it at least.

Let’s look at Eastern Europe: how should we view Vladimir Putin’s position since the beginning of the war?

The radicalization we see in Putin has evolved over at least the past ten years. Since 2012 at the latest, we have been able to identify a return to autocracy within Russia that goes hand in hand with ideas of revanchism, nationalism, and imperialism. The recent history of Russia’s wars in Chechnya, Transnistria, Georgia, and in Ukraine since 2014 bear this out, as does Russian intellectural life. In think tanks and networks close to the government, identifiable for example from topics discussed in the Valdai Club, this trend has been on the rise for some time. Putin and the Kremlin obviously imagine themselves in a fight against imperial disintegration—and in doing so, they only make it all the more evident.

How relevant is your research on dealing with conflicts and wars?

Research can help to perceive certain developments sooner. Academia can identify new dynamics in a society and be an early warning system for conflicts as well. It can also pinpoint particularly vulnerable groups within a conflict and suggest measures for resolving conflicts. How far academic recommendations are translated into practical policy is quite a different issue. In its analyses, academia can also make a distinction between desirable and realistic outcomes—and do so more objectively and rationally than is the case in public discourse.

You are the German director of the Centre for German and European Studies (ZDES/CGES) based in Bielefeld and St Petersburg. Collaboration with your Russian partner university is on hold. How are you handling this situation?

We suspended working with St Petersburg University immediately after the Russian invasion began. The vast majority of our Russian staff and cooperation partners fled Russia because they opposed the Russian war of aggression and faced political repression. Institutional cooperation with Russian research facilities in the field of social sciences would not be very fruitful at present. Russian universities and research institutes are under government control, and at the present time, it would not be possible to cooperate freely and openly in terms of content. One of the main focuses of our work is now on the activities of the Bielefeld Centre. Here, we are also working together with refugee academics.

About the series

In this series of interviews, academics at the university explain their assessment of the war in Ukraine from the perspective of their own disciplines. Previously published interviews:

- Professor Dr Andreas Zick (25.03.2022): ‘We need to know where more violence is brewing’

- Professor Dr Frank Grüner (31.03.2022): ‘Putin is distorting history for his own ends’

- Professor Dr Véronique Zanetti (14.04.2022): ‘A nuclear war must be avoided at all costs’

- Dr Leif Seibert (23.05.2022): ‘Putin and Kirill benefit from mutual legitimation’

- Assistant Professor Dr Julian Hinz (14.06.2022): ‘Russia has gambled away its economic future’

- Professor Dr Christina Morina (21.07.2022): ‘The Eastern European perspective has been neglected for too long’

- Professor Dr Antje Flüchter (21.10.2022):‘Comparing with the Holocaust is relativizing history’

- Professor Dr Peter Bernard Ladkin (14.11.2022): ‘The Hollywood image of hackers is misleading’