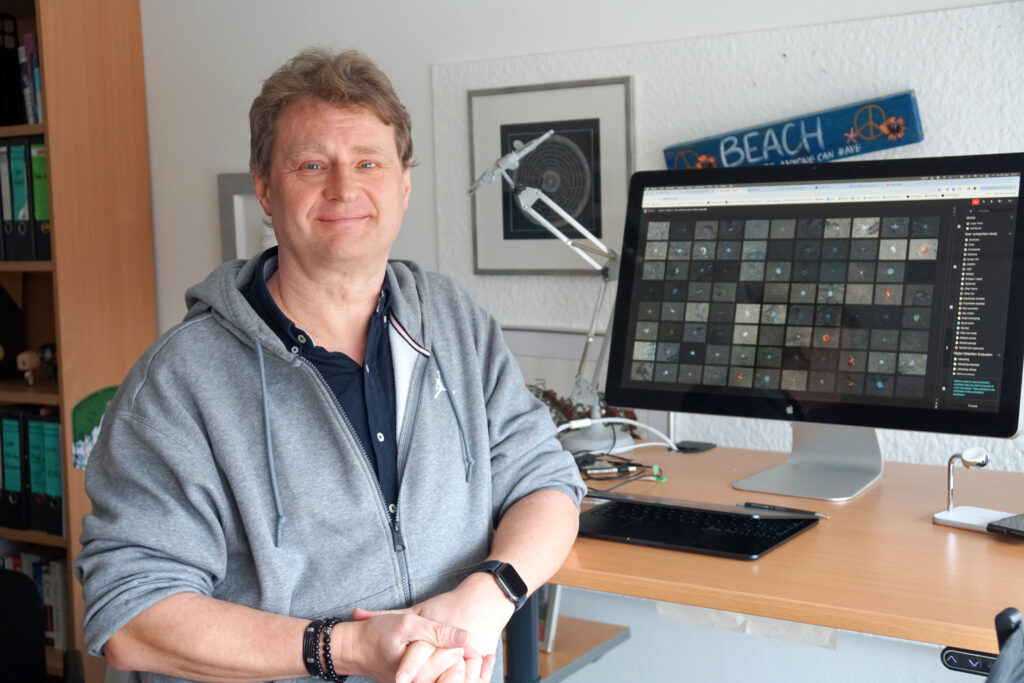

Analysing terabytes of video and image recordings from the deep sea and recognizing and segmenting all the creatures depicted—this would be extremely time-consuming and hardly possible with the untrained naked eye. However, these masses of image material must be viewed and analysed if we are to keep track of biodiversity in the oceans. Professor Dr Tim Nattkemper from Bielefeld University’s Faculty of Engineering has been working on AI-based analysis platforms for underwater images for more than 15 years. The university is one of a total of 19 cooperation partners in the ongoing EU project ‘BioProtect’ that aims to improve the protection and restoration of biodiversity in European seas.

Not only marine pollution and fishing but also shipping in general are damaging ecosystems, reducing biodiversity in the oceans, and fuelling global warming. The international team in the BioProtect project aims to provide impact-oriented solutions to preserve biodiversity and mitigate climate change and thereby help to achieve the relevant targets of the EU Biodiversity Strategy for 2030. The extent to which human activities endanger diverse marine animals is not yet fully understood. The researchers are recording and modelling these stress factors. This will enable them to advise policymakers on measures to successfully preserve biodiversity. ‘The underwater biosphere is significantly larger than the terrestrial biosphere,’ says Tim Nattkemper. That makes it difficult to determine what organisms are to be found in the sea and in what abundance. Professor Dr Tim Nattkemper and his team at Bielefeld University are involved in two aspects of the project: data collection and citizen science projects.

© Jana Haver

The interdisciplinary EU project integrates different spatial scales and data sources. Bringing together and analysing all the data collected is a challenge for this consortium of scientists from eight countries. In addition to collecting environmental DNA and analysing DNA traces of bacteria, fish, and other organisms in the water, image analysis plays a key role. Hundreds of hours of video material are being recorded at five different locations. Tim Nattkemper and his team are using artificial neural networks to analyse these masses of images and determine what animals can be seen and how often they are seen. For example, artificial intelligence (AI) is used to mark conspicuous sections in the images that can then be analysed by marine biologists.

© private

Analysing underwater images with artificial neural networks

Tim Nattkemper’s research focuses on AI-based underwater image analysis. Cameras attached to the cooperation partners’ special ‘underwater drones’ (so-called ‘ROVs’: Remote Operated Vehicles) record video material several 100 metres deep in the water. The Bielefeld bioinformatician then analyses this video material together with a postdoc. The underwater drones often float directly above the seabed and take photos at regular intervals. However, most of these images are brown or noisy, and recognizing individual creatures requires high magnification. The AI automatically scans the images and flags the relevant areas, thereby saving an enormous amount of time.

© Bielefeld University

To be able to compare the different locations of the project over a longer period of time, Tim Nattkemper is working on an overview documenting how often, when, and where which creatures are found A biodiversity index, as it is called, is being defined for this that can be used to determine the quality of the ecosystem in the long term. ‘Not all living organisms in water are already known,’ says the bioinformatician. ‘We don’t even know how few of the animals and individual species in the deep sea are already familiar to us.’

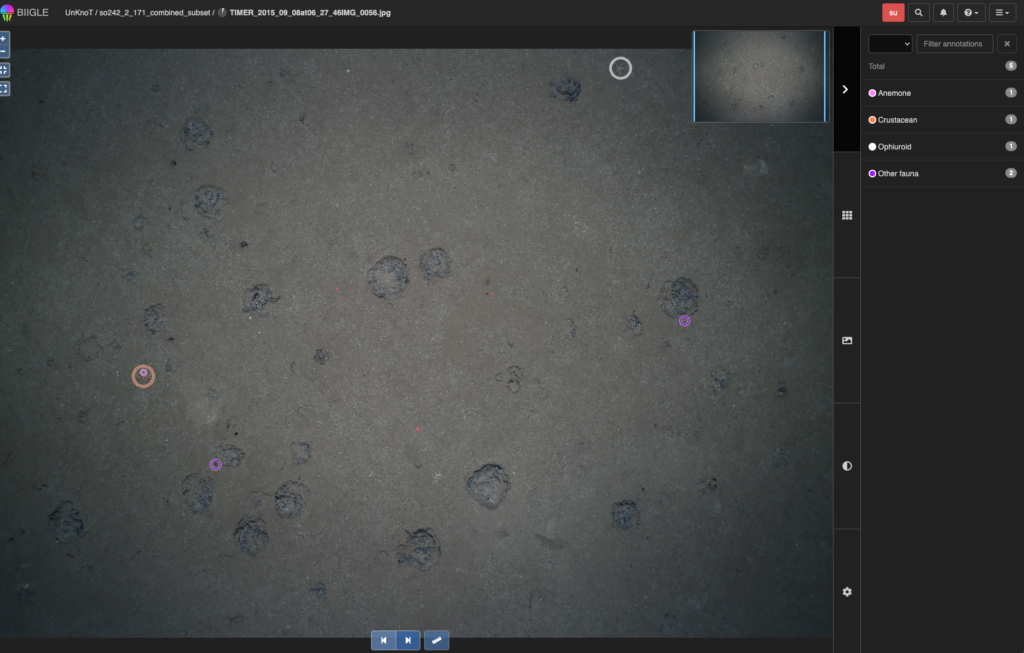

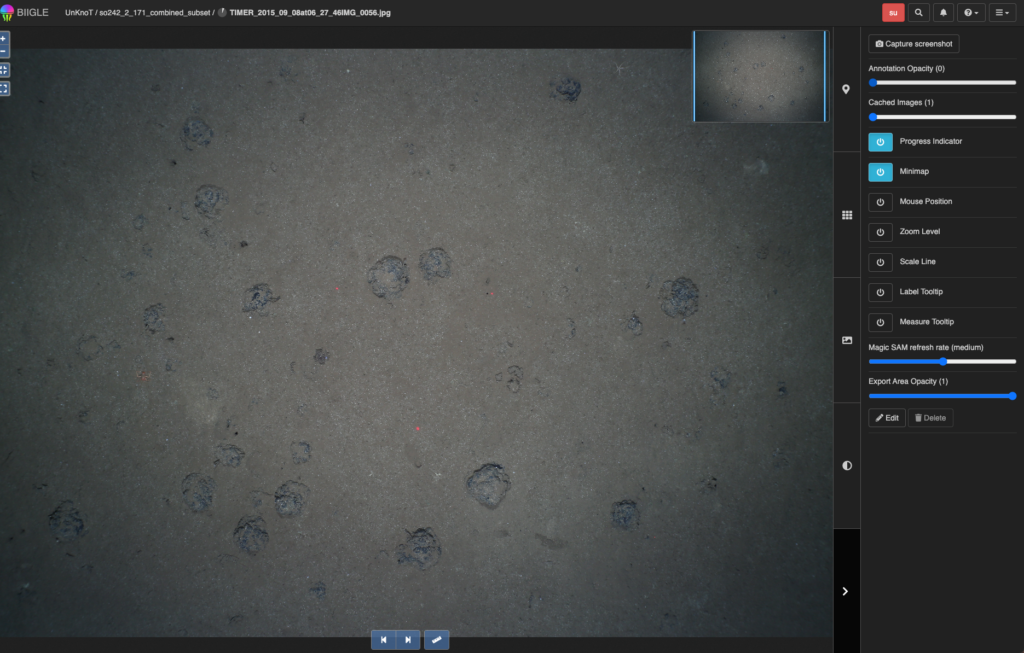

About seven years ago, Tim Nattkemper developed a new version of his online system BIIGLE. This online platform has around 3,000 users worldwide, mainly marine biologists. BIIGLE is an image database system that makes it easier for biodiversity researchers to analyse their images and videos together, and it also offers several AI-based tools for this purpose. The professor explains: ‘Users upload their photos and videos and can then easily label them manually or share them with colleagues.’

© private

© private

Training AI with little annotated data

Tim Nattkemper trains the respective AI with specific training data in order to develop an artificial neural network. The data represent a particular challenge, because labelled data are very scarce compared to other algorithms such as those in social media. Only trained marine biologists can determine what exactly can be recognized in the images. This means that the AI has to be trained with very little annotated data. ‘Hence, the AI is first shown unlabelled images and given game-like tasks to perform,’ explains Tim Nattkemper. ‘It has to solve these tasks with the unlabelled images—for example, by filling in deleted partial images in new and “meaningful” ways.’ This teaches the AI a lot about this image area. Only then do we add labelled data. ‘We usually train the self-supervised learning algorithms we work with to address one specific task,’ explains Tim Nattkemper. He will also train artificial neural networks to analyse data for the EU project and probably use the BIIGLE software for this.

Making the public more aware of the need for marine biodiversity

‘It’s not so easy to get the public interested in biodiversity issues,’ says Tim Nattkemper. ‘For most people, climate change, global warming, and the weather are more tangible than some kind of bugs facing extinction.’ To protect biodiversity in the oceans, it is essential to increase public awareness on this issue. Citizen science projects—that is, projects in which citizens get involved—are therefore an important part of the EU project. Tim Nattkemper hopes to build on the results of a project that was funded by the EU’s Erasmus+ programme: together with four other institutions, coordinated by a small organization called InterChange, Tim Nattkemper has developed the citizen science software ‘BIIGLE.party‘ in the ‘Into The Deep‘ project. Working with the platform is anonymous, which means it could also be used in schools in the future. To motivate people to take part, the platform is equipped with what are termed gamification functions—that is, game-like elements designed to encourage its use. ‘Participants view real images, for example, from an observatory off the coast of Barcelona, and they are asked to solve specific tasks such as recognizing three types of fish and classifying them correctly,’ says Tim Nattkemper. ‘The feedback we’ve received has been great. The new tool works smoothly and participants are enthusiastic about it.’ He will also offer such citizen science activities in the new EU project. An adapted version, ‘BIIGLE.party’, can be used to analyse, for example, the images taken in the Azores.