In the age of digitization and digitalization , travelling to archives could seem somewhat behind the times. Nonetheless, there are still immense advantages to researching locally instead of examining a digital image of a resource from afar. In the Collaborative Research Centre 1288 ‘Practices of Comparing. Ordering and Changing the World’, archives and the research trips they involve play an important role in research in the humanities and in the acquisition of knowledge. After all, only the experiences, media, and artefacts on site make it possible to explore completely different, additional research areas. Doctoral students Angela Eva Gutierrez, Jacob Bohé, and Mathilde Ackermann-Koenigs report on their research abroad and their experiences in the respective archives. They give an insight into why travelling to archives is part of their research work, show pictures from their working environment, and explain what they found so special about it.

Research on race and racism in Cuba

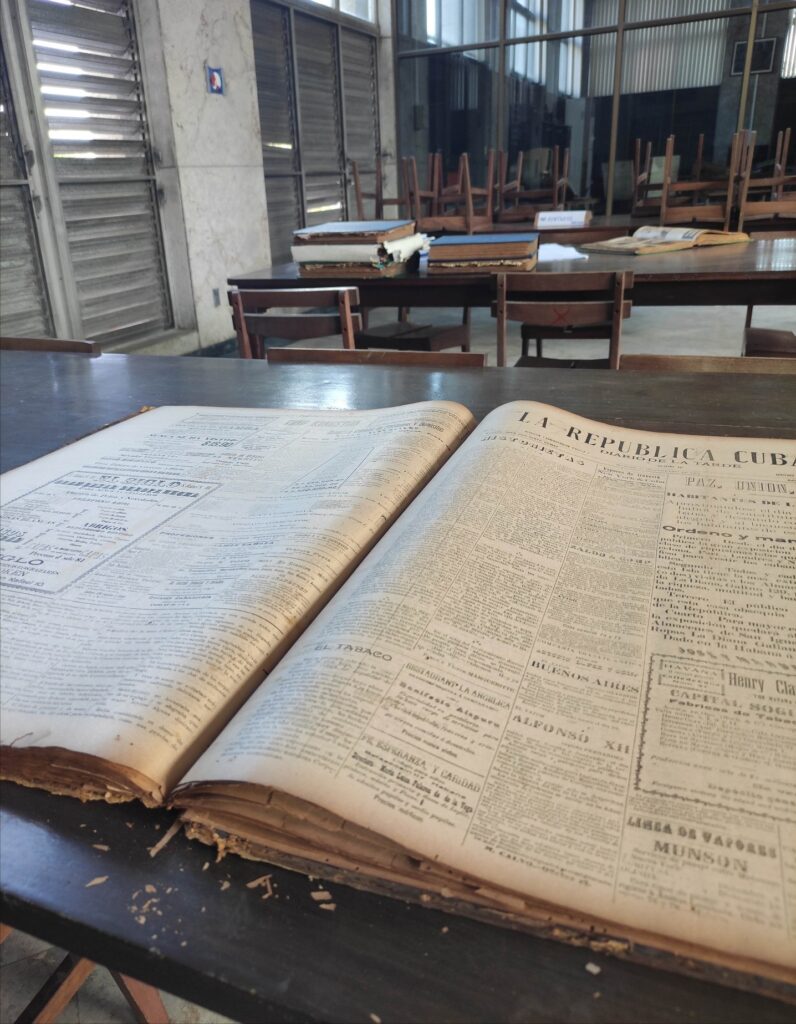

In Cuba, Angela Eva Gutierrez researched newspapers and magazines, some of which had not yet been digitized, in order to obtain important information for her thesis.

‘My thesis topic deals with race and racism in Cuba—from the abolition of slavery in 1880 (officially 1886) to the 1912 massacre. My focus is on the journalistic community, especially Afro-Cuban journalists, who shape journalism by producing and disseminating reports on current events which, in turn, shape public perception and discourse. Comparisons play an important role in how we categorize and position ourselves in the world, who we identify as different, and how we construct hierarchies. Therefore, the subject of my investigations is how journalists compare, what they do when they compare, and what is created by these comparisons. My research questions include how journalists deal with the terms ‘race’ and ‘racism’ in their newspaper and magazine articles. What role do comparisons play in the debate? What types of comparative practices can be identified, and how do these change over time?

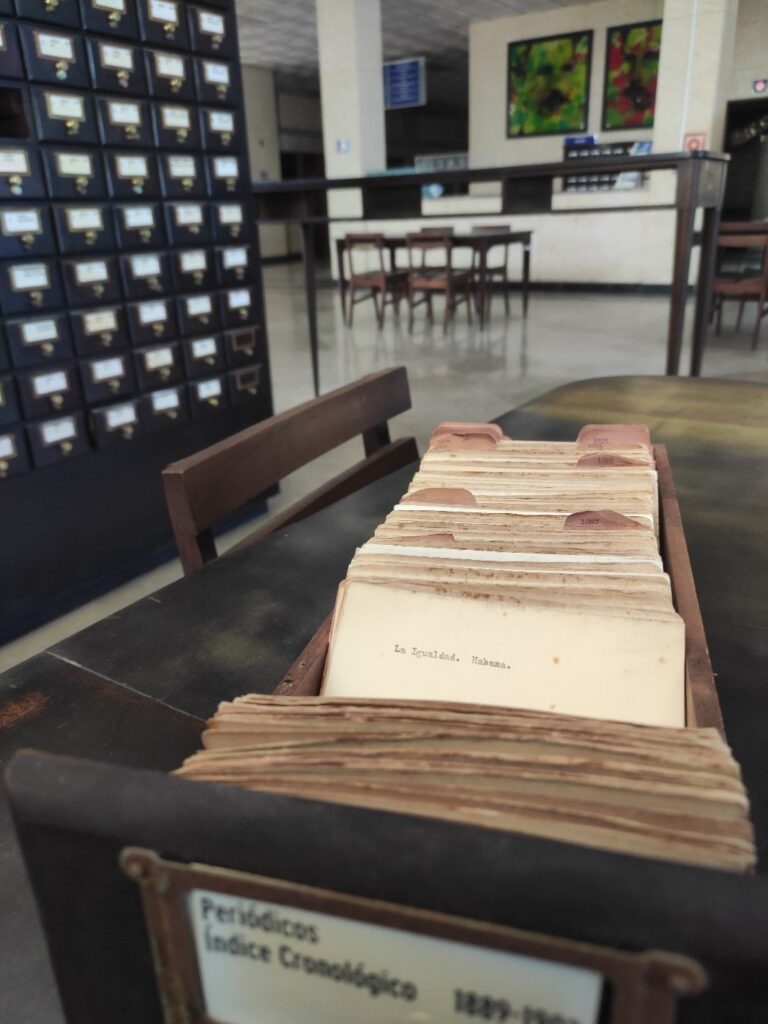

That’s why it was important for me to travel to Cuba to look for these newspapers and more information about journalism in the early republic. I visited the National Archives and the José Martí National Library where I found a whole series of newspapers. Naturally, I was also able to find some in digital form, but for me, it was important to be in the local archive. Not only to have the experience of searching for documents and getting used to a completely different system of organization, but also to have the actual media before me. In the end, I was able to find newspapers that I wouldn’t have been able to find digitally. Unlike digital documents, there is something special about interacting with the materials themselves: not only with the original document, but also with the desk I was sitting at, with the smell of the old books, or leafing through the card catalogue.

Visiting an archive is a test in adaptation and the reward is the material. For example, the quality of the aged paper, the smell, and the legibility of the words. Just like I feel when I’m reading a book, when I’m out there doing research, holding something in my hand, and being in that space—it’s precious. Archive visits also provide the opportunity to exchange ideas with others about your research. This dialogue is also important. Ultimately, a visit to an archive is worthwhile for a number of personal and professional reasons.’

In the archives of banks and insurance companies

Through his exchange with the archivists at the Deutsche Bank archive, Jacob Bohé was able to gain insights that gave him new and necessary perspectives on his field of research.

‘My trip to the Deutsche Bank archive in the summer of 2022 wasn’t just the first archive trip as part of my thesis, but also my first archive trip ever. As a social scientist working on a historical thesis project, this was a new and special experience for me. Since then, I have travelled to a number of private and national archives. There are marked differences in how private and national archives work—at least in my experience.

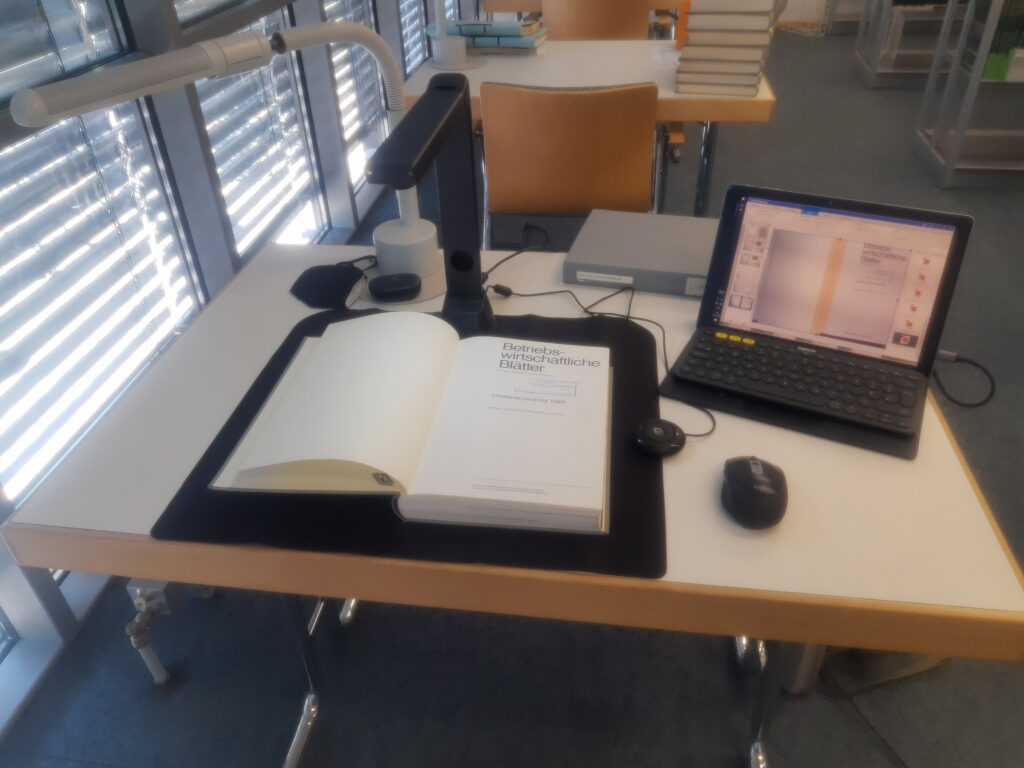

National archives, such as the Federal Archives in Koblenz or the State Archive in Hamburg, have publicly accessible indexed records on their websites. Therefore, I was able to carry out my research at these archives independently, and any exchange with the archivists remained quite limited. This research process was very different at the archives of the banks and insurance companies. Here, they have indexed records that are generally not publicly accessible—at least at the archives I had contact with. This made it necessary to liaise closely with the archivists at the beginning. Unlike national archives, where you can initially order files at random, here you need a concrete idea about which files you are looking for. Archivists then carry out the actual research work in the respective archive collections. The process for reviewing files for my thesis was very similar. I always had to visit the archives, because they had digitized very few files. I had to view the documents on site and digitize the information I needed myself. This is often a monotonous task, but it does allow you to take that first important look at relevant and adjacent documents. In some of the private archives I was also able to consult the library collections there. It was worth taking a look at the collections there to find out which literature was actually used, but also to access additional literature.

That’s how I came across a few specialist titles that were difficult or even impossible to obtain even via the nationwide interlibrary loan system. Engaging in dialogue with the archivists from the banking and insurance archives was also one of my best experiences during on-site visits. By talking to the people that work there, you can often learn more about the systematic arrangement of the archives and how, in my case, structures in the banks or insurance companies actually function. This not only helps to refine research enquiries, but also to further develop the subject matter of your own project. The opportunity to interact more intensively with archivists was immensely important for me and significantly helped my research project. By sharing information with the archivists, I even had the good fortune to receive documents that had not yet been catalogued. These files are some of the most important archival materials I currently have for my thesis project. These include some relevant documents as well as documents that have not yet been analysed academically. Visiting archives was worthwhile for me not only to look through and digitize files, but also to learn more about banking and insurance archives through discussions with archivists, to further develop my research topic based on their specific collections, and, last but not least, to obtain new archive materials. Without the documents from the archives, it would be almost impossible for me to complete my thesis, but above all the necessary perspectives of the banks and insurance companies would be missing from the work.’

Previously unexamined archives in Haiti

Mathilde Ackermann-Koenigs is researching Haiti’s independence in the 19th century and the consequences this had for local plantation owners. She came across resources that had not yet been digitally recorded.

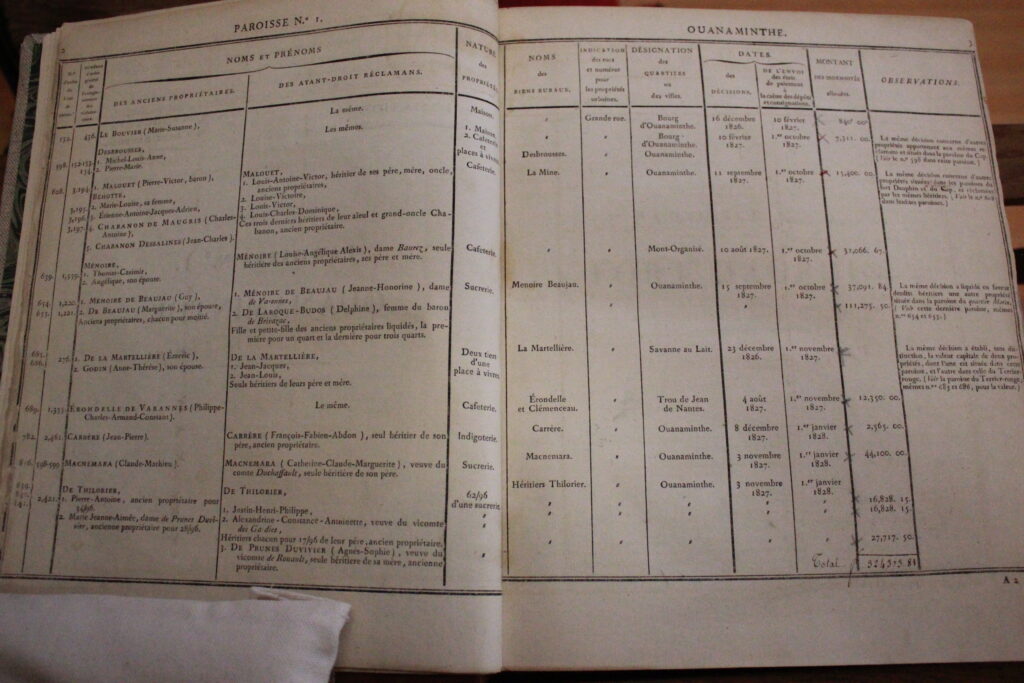

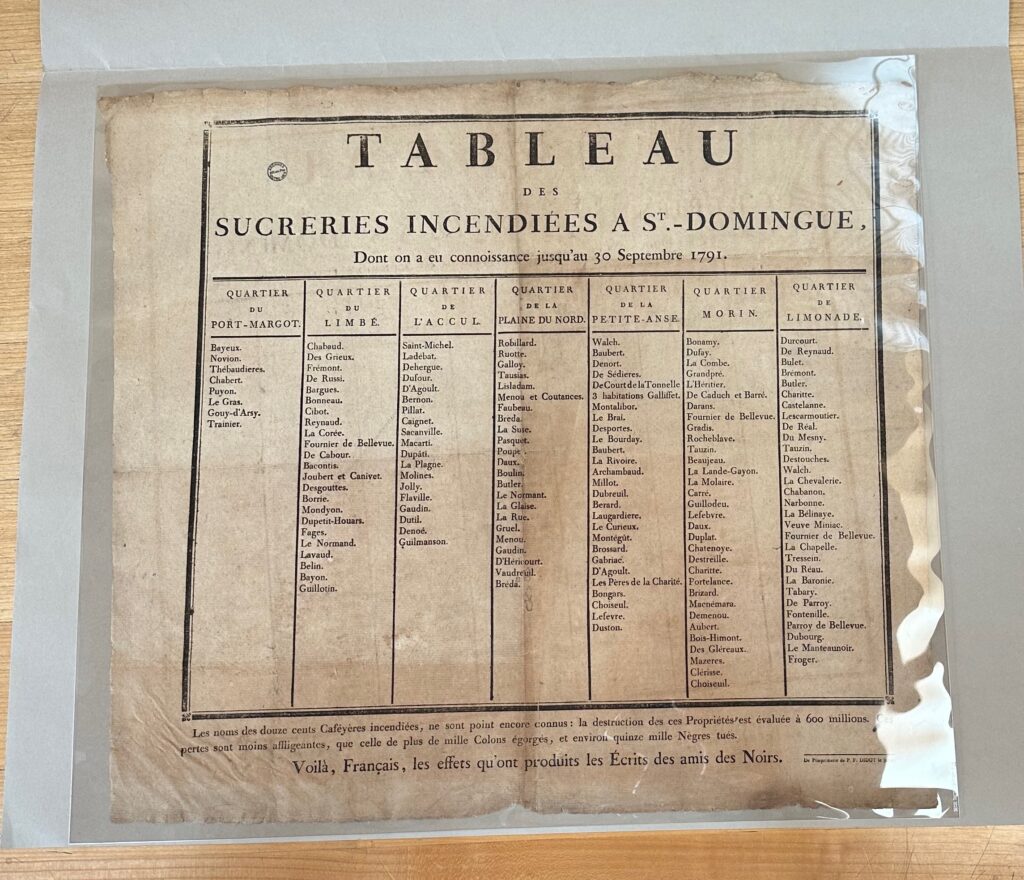

‘My doctoral project focuses on how former French plantation owners were compensated after Haiti gained independence. On 17 April 1825, after almost a decade of negotiations, the recently crowned King Charles X declared the French part of Saint-Domingue, today’s Haiti, fully independent. This proclamation was the culmination of more than twenty years of struggle for independence by the former colony, which had already declared its independence in 1804. This independence was a direct consequence of France’s defeat by the Haitian troops that ended the Haitian Revolution.

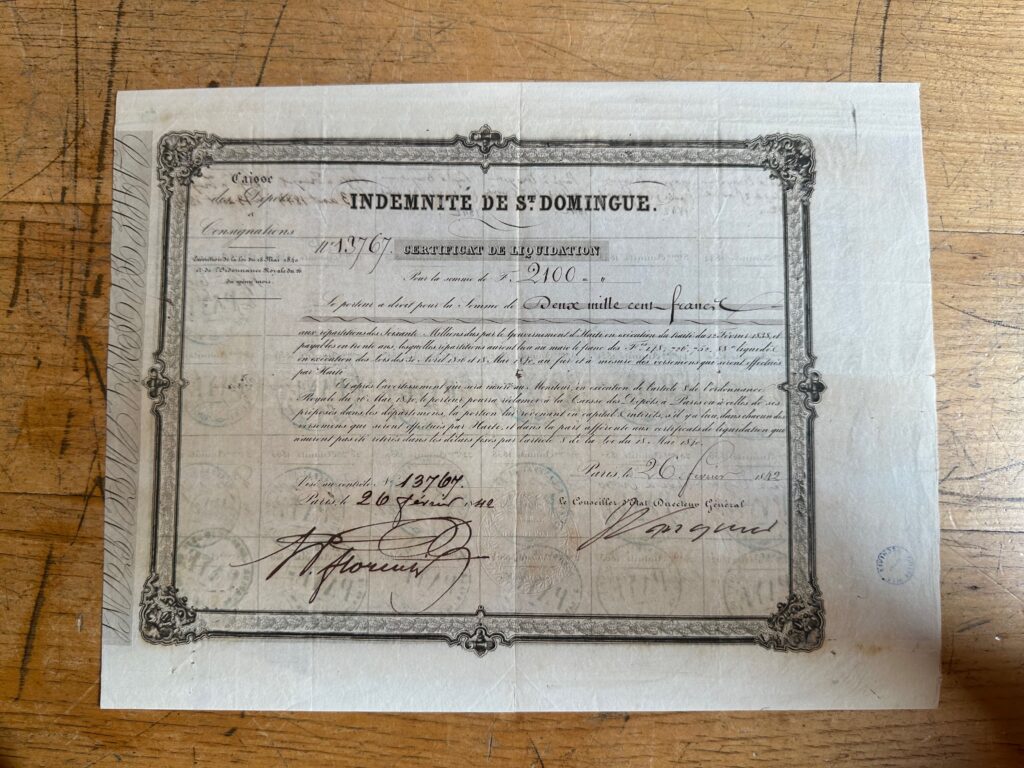

However, conceding independence was not just a peaceful agreement. It carried both political and economic conditions: Haiti was to remain within the French sphere of influence, taxes on French goods and ships were to be reduced, and an indemnity payment of 150 million gold francs was to be paid to the French owners who had been driven out. This financial obligation led to protracted diplomatic and economic entanglements between the two countries well into the 20th century.

Although payment was originally to be made over five years, this period was extended to 83 years. This ‘delay’ resulted in an enormous number of documents of various kinds. The aim of my archive trips so far has been to record the history of these documents. The archival history of this indemnity is fragmented and complex. Documents are scattered across various institutions. For example, the families of former colonists had to address their enquiries to the colonial archives, now known as the Archives nationales d’outre-mer. The payments were made by the ‘Caisse des Dépôts et des Consignations’ in cooperation with the Ministry of Finance. In addition, political upheavals in 19th-century France led not only to the destruction of archives (as during the Paris Commune of 1871) but also to institutional changes.

Despite the growing digitization of archives in France, most documents are not digitized. This makes physical visits to archives essential. As well as being able to assess the physical condition of the documents—paper type, ink, format—on site, which also says a lot about the original purpose of the document, it also allows direct interaction with archivists. During my last trip, I was made aware of previously unexamined archives, an invaluable resource for my work.’