If you ask people who know him, they describe Gerhard Sagerer as creative, focused, and communicative. And time and again, they say that he is unconventional, always wanting to get things moving. He himself also underlines his penchant for using data as a basis for decision making. On 30 September, after 33 years at Bielefeld University, the past 14 of them as its rector, Gerhard Sagerer is retiring. We look back on his eventful time at the helm of our university.

‘An immensely important development for universities in NRW was what is known as the Hochschulfreiheitsgesetz [Freedom of Institutes of Higher Education Act], which came into force on 1 January 2007,’ recalls Sagerer. ‘When I became rector in 2009, this law was just starting to have its impact: in one stroke, we were given much more autonomy, so that today we can do things very differently. We have more opportunities, but also more responsibility.’ Sagerer has never shied away from responsibility and he loves creative freedom. ‘I had the right setting for my projects.’ And his agenda was all about change and growth.

Challenge: rising student numbers

© Bielefeld University/Michael Adamski

During his 14-year tenure, the number of students at Bielefeld University has increased by almost 30 per cent. The teaching degree programme has even registered an increase of over 70 per cent. The nationwide increase in student numbers was politically and socially desired, but had to be managed by the universities. ‘It took a feat of strength. This growth was only possible as a team effort—by the rectorate, administration, and the faculties.’ What had transpired?

Starting in 2007, the universities received money from the federal and state governments to create new study places, but only in the form of temporary special funds. ‘Initially, investment was made in infrastructure and projects, and additional staff were hired mostly on a temporary basis for the duration of the special programmes. I thought that was wrong.’ Sagerer was convinced that public policy would not stray from this chosen course. His theory was that the additional money would ultimately become permanently available. But how should the faculties deal with the undeniable lack of planning certainty? Sagerer’s creative response to this was the ‘UNIplus’ personnel offensive in 2016. ‘We needed additional staff to cope with the tremendous increase in student numbers while simultaneously maintaining our quality standards in teaching. This is simply not possible with temporary contracts. Especially not on the professorship level.’ Sagerer identified professors in each faculty who would be retiring in the coming years. In a strategic collaboration with the faculties, a large number of these professorships were filled in advance. This immediately improved the supervision situation for students and strengthened the university’s research profile. Firm plans were made with the special funds for only a few years. After that, the programme afforded the flexibility to reduce the number of positions back to their original level, or to hire additional professors should the funding be available again. It was a strategy that became a success story. ‘I am delighted that bringing forward professorship appointments has now become common practice at our university. Bettina Lang, director of university development, did a lot of convincing in countless meetings.’ The idea ended up becoming a standard instrument of strategic organizational development.

At this point, Sagerer has more figures at hand that document the university’s growth: ‘In the 14 years of my tenure, the number of professorships has risen from 270 to 363; and as rector, I presented 273 certificates of appointment. The financial volume has also increased by 80 per cent.’

Professorship appointments—a key element of success

‘Professorship appointments are pivotal to a university’s success—these staffing decisions have a massive impact on how research initiatives develop, for example.’ Computer scientist Sagerer therefore sees a professorship appointment as a complex process from identifying the need and naming the necessary chair to the advertisement, selection, appointment negotiation, and the appointee’s start. Today, the university takes a much more strategic approach to filling professorships. Appointments are preceded by intensive discussions on the development of the respective faculty and core research interests. Professorships are then often advertised for different levels (W1, W2, or W3) in order to increase the number of applicants. This is accompanied by market research, and possible candidates are approached systematically. The focus is always on attracting more female professors—a matter of some importance for Sagerer. The procedures are overseen by the vice-rectors to ensure close coordination with the rectorate. And once the appointment has been made and the person starts at the university, there is now an attractive inplacement programme called ‘Off to a good start’ that is used by all new appointees. ‘These measures are designed to ensure that the faculties can actually reach the right candidates with their advertisements, attract them, and also retain them in the long term.’

More opportunities for junior academic staff

However, professorships are not all Sagerer has in mind. In the current electoral period, together with Vice-rector Marie Kaiser, he has focused explicitly on mid-level academic staff. The working conditions of junior academic staff in Germany have long been a topic of discussion, and with the 2021 #IchBinHanna (‘I am Hanna’) campaign, the topic also came to the attention of the general public. For Sagerer, employment contracts for mid-level academic staff have been a subject in need of reform for some time. ‘However, we cannot hide behind legislators; as universities, we must also take responsibility ourselves.’ With the ‘Academic Tenure’ career path, Bielefeld University wants to establish permanent positions in mid-level academia as an attractive option for academics. The corresponding concept was adopted after in-depth discussions with the faculties and various committees. The number of positions with academic tenure is still small, but Sagerer is certain: ‘This category of positions creates opportunities that the faculties will embrace.’

Medical School

© Bielefeld University/S. Sättele

The establishment of the Medical School OWL is probably the most prominent project associated with Sagerer’s tenure. After the first failed attempt in 2010, when the CDU-led state government was voted out of office and the successor government did not pursue the issue, Sagerer did not abandon his conviction that the idea was right and essential for the region. And a new faculty would also be a boost for the university. ‘I was always sure that the medical school would get back on the political agenda.’ Once again, his intuition proved correct: when in 2017, after the state elections and a new change of government, establishing a medical school was back on the agenda, he was prepared and used all the means at his disposal along with his political contacts to bring it about. He was able to enter negotiations with the state government and present concrete ideas. They appreciated his straightforward manner and many a difficult situation was resolved constructively. ‘My main priority was that the new faculty should not have a negative impact on the other faculties. Medicine should and can only exist with its own additional funding. It must be sufficiently financed by the state.’ He accomplished this.

Sagerer is very aware of the importance of setting up the medical school and his role in it. He is proud and convinced that the Medical School OWL is well designed and planned. The new expansion is working, he says, and the benefits—also for the university—are already becoming visible. And, according to Sagerer, this is not just down to him, but also to the development team around Dean Claudia Hornberg.

He is at least just as happy to talk about other projects and plans that are not as high profile but have far-reaching effects on the development of the university and the region. ‘Beyond medicine, the fact that we took the reform of the nationwide training of psychotherapists as an opportunity to also massively increase the number of study places here has almost gone under the radar—here, too, the status quo effect will ensure that the situation regarding therapeutic care in Bielefeld and OWL improves.’ Bielefeld University has thus become one of the largest locations in Germany for training psychotherapists. Creative solutions were again needed to make this happen: for example, the university moving its psychotherapeutic outpatient clinics into the renovated Telekom high-rise (H1) in the city centre: 2,000 sqm over six floors.

Using budgets to trigger activity in faculties

‘The introduction of the funds distribution model was one of the most difficult projects of my entire tenure, with numerous critical discussions, a lot of emotion, and definitely great risks.’ Sagerer is firmly convinced that if you want to inspire major change in the faculties, the best way to do this is through financial incentives and performance-based funding. ‘I knew that we had to change something—the tide had turned against Bielefeld University, we were no longer as successful as we used to be in competing with other universities, and, in my opinion, the faculties lacked strategies for the future.’ At the same time, faculties also need planning certainty for their budgets. In 2015, against this tense backdrop, he and the responsible vice-rector, Reinhold Decker, together with the chancellor, Stephan Becker, spent a number of months discussing the matter with the various committees. There were heated debates about goals, principles, and percentages. And while the controversial discussions between the rectorate, faculties, Senate, and University Council were still in full swing, Sagerer’s re-election was approaching. The funds distribution model became a central topic of the election. ‘In the end, we reached a good compromise on the funds distribution model, and I was also re-elected,’ Sagerer sums up with a smile. ‘In retrospect, I can say that we took the right path. Today, we have much more transparency in the allocation of funds, our incentive schemes work, and the faculties have sufficient planning certainty and now also regularly address their strategic orientation.’

Listening to students

During his time as vice-rector for studies and teaching (2001 to 2007), one painful experience for Sagerer involved the conflicts with students when tuition fees were introduced in 2006. Afterwards, as a result, the students’ relationship with the rectorate was strained. As rector, he wanted to change that. At the time, things were not looking good: his inauguration had already been hindered by protests from students and had even had to be abandoned. They were not demonstrating against Sagerer, but wanted to draw attention to what they saw as problematic developments in the education system by taking part in a nationwide education strike. But Sagerer learnt from this experience: ‘We need to have a good relationship with our students, we need to know what is bothering them, and where the problems are. This is the only way we can ensure good study conditions and functioning relations in the long term’, says Sagerer. ‘I take student opinion very seriously and have therefore focused on regular, open communication formats.’ Meetings with departmental student representative committee were initiated, and there are now regular meetings with AStA [Student Union] and the students in the Senate. His door has always been open for student representatives. And even in the event of critical issues, his preference has been for direct dialogue. Most recently this was with students who occupied a lecture hall to draw attention to demands for sustainability. Today, problems are discussed in a positive and cooperative mood. This appreciation and the insight that the university must bring students emotionally closer to the ‘study experience’ is also reflected in events such as Graduates Day or the Campus Festival. Sagerer personally campaigned for both of them and also opposed critical voices that did not see such events as being the university’s responsibility. ‘A degree programme is more than courses and exams—for students, this time represents an important stage in their lives.’ And at the same time, such events also make the place of study and the university more attractive.

Harmonious interaction—a matter close to his heart

© Bielefeld University/Mike-Denis Müller

Interestingly, when reviewing his achievements, Sagerer highlights 2019, the year of the university’s 50th anniversary. ‘Preparing “Our Mission”, planning and implementing the anniversary programme, and the university’s new corporate design were important opportunities to communicate and discuss the profile of the university internally while simultaneously enhancing its public image.’

The harmonious interaction that he has enjoyed so much, especially during the anniversary year, is very important to Sagerer. He needs to feel that people are happy at the university and identify with it. This need is also reflected in his frequent walks through the university’s main hall and across the campus. During his walks, opportunities arise to engage in conversation with employees and students. He listens and asks questions. ‘As rector, you run the risk of losing contact with the people at the university,’ he explains. ‘I wanted to avoid this at all costs.’ And the importance he attaches to the interaction between academic, technical, and administrative staff was demonstrated once again at the staff party on 25 August, when he expressed his wish that the groups should respect each other and value each other’s work.

For the city and the region

© Bielefeld University

Sagerer is also a networker. And that means he fits very well into a region that also draws its particular strength from diverse networks. This mindset worked to Sagerer’s advantage and he made good use of it. On his initiative, for instance, the state universities and institutions of higher learning in East Westphalia-Lippe co-founded the Campus OWL association. Originally conceived as a communication forum, the association has now also become a platform for joint projects in the areas of research, teaching, and studies. Sagerer also focused on industry in OWL, seeking contacts and exchange. For example, he saw the opportunities offered by the ‘it’s OWL’ Cluster of Excellence and used this to establish contacts between the university and companies with which there had been no connection before. He also joined Chancellor Stephan Becker and Vice-rector Reinhold Decker in promoting the founding of the Bielefeld Research and Innovation Campus (BRIC), a joint limited liability company of Bielefeld University and Bielefeld University of Applied Sciences, the city, and the East Westphalia Chamber of Commerce and Industry, whose aim is to promote cooperation between academia and industry. Collaboration with Bielefeld Marketing was also intensified. The university is an active participant in the ‘Bielefeld Partner’ supporter programme and is involved in setting up the ‘Wissenswerkstadt’. Sagerer has also always sought intensive exchange with political decision-makers. He certainly also benefited from his activities and his contacts as chairman of the State Rectors’ Conference. In the political arena, he is highly regarded as a competent and reliable contact person.

And what about research in Bielefeld outside the university? What are the prospects for such an institute? Sagerer can also report progress here: ‘We have advanced well by taking small steps; for example, since 1 August, we have had a department of the Jülich Research Centre from the Helmholtz Association here on campus, comprising more than 20 people.’ A joint professorship with Fraunhofer IOSB-INA in Lemgo is also in place, and there are very close collaborations with Helmholtz Munich as well as the Max Planck Institute for Mathematics in the Sciences in Leipzig. As for the Leibniz Association, Bielefeld University runs a Leibniz Science Campus here on site together with the German Institute for Economic Research in Berlin and there is a joint professorship with the Leibniz Institute for Analytical Sciences ISAS. Furthermore, the federal government is supporting the Conflict Academy, which is currently being set up.

© Bielefeld University/Michael Adamski

Excellence Initiative and coronavirus

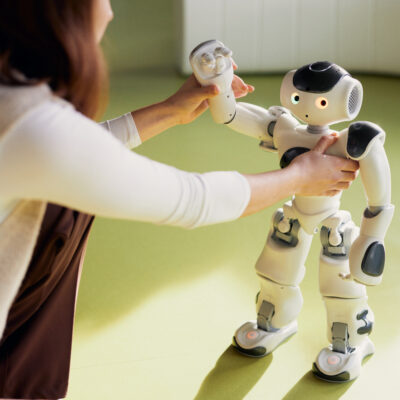

Gerhard Sagerer is a successful research scientist. His core research interests include cognitive and social robotics, human–robot interaction, and intelligent systems architecture. He was deputy spokesperson for the Cluster of Excellence Cognitive Interaction Technology (CITEC). His mission: cutting-edge research. For this reason, one detail of his final summary weighs particularly heavily: ‘The fact that we did not manage to acquire a follow-up cluster after our successes in the first two rounds of the Excellence Initiative and the discontinuation of CITEC funding was a bitter defeat,’ Sagerer openly admits. However, the rectorate learnt a lot from this and reacted accordingly. ‘After a very intensive and objective analysis, we made important adjustments and have hopefully created the prerequisites for success in the current round,’ says Sagerer.

He sees the period of the coronavirus pandemic as another dark hour of his tenure. ‘It hit me very hard when our university was effectively empty for months.’ However, it is also typical of the outgoing rector that he finds something positive even in this situation: the dedication of all employees, the willingness to accept the situation and to find flexible solutions—he found that very impressive. ‘It became very clear during this crisis just how much our colleagues identify with their university. They assumed responsibility—especially for our students. The students had to endure a difficult time, but they willingly accepted the necessary measures. That made me feel proud.’

This pride and a great sense of satisfaction with his contribution to Bielefeld University’s development are clearly evident in Gerhard Sagerer. However, he repeatedly emphasizes how dependent a rector is on motivated colleagues in the rectorate, the faculties, and in the administration. ‘Without the support of so many colleagues—often above and beyond what might be expected—I would never have been able to achieve as much.’

And another point is central to his understanding of the office of rector: ‘As a university, you shoulder responsibility for social developments. For me, that has always been a guiding principle—for example, when setting up the Medical School, expanding the teaching degree programme and psychotherapy, as well as strengthening relations with businesses.’

There is not enough time in one conversation to highlight all the important projects and developments. It is not possible to do a complete review of a 14-year term in office. But one detail is still very important to him at the end of the interview: ‘I need a functioning and harmonious environment—from the secretary’s office to the rectorate—to be able to work well. During these 14 years, we have had a high degree of continuity in a lot of the positions here, including the vice-rectors. I am very grateful to all my colleagues for putting up with me for so long.’

© Bielefeld University

On 30 September, Gerhard Sagerer retires as rector and hands over his office to his current deputy, Angelika Epple. He does not want to give his successor any tips. Only to say: ‘I wish her every success, the required courage, the time for meaningful conversations, and the necessary slice of luck. There’s always plenty to do at this fantastic university.’