Whether it is polar bears in the Arctic, gorillas in Uganda, or sea lions in the Galápagos, Professor Oliver Krüger undertakes expeditions to faraway locales to observe animals deep in the wild. As a behaviour researcher at Bielefeld University, Professor Krüger seeks to understand how different animal species adapt to shifts in the environment and climate change. One thing he never leaves home without: his camera, to capture those extraordinary encounters.

Oliver Krüger has turned his passions – nature and photography – into his profession. ‘And the great thing about my work is that I always see something fascinating when I observe animals,’ explains the biologist –whether in his own backyard, in the Teutoburger forest, or further afield. That said, there are admittedly a few special spots around the globe that get the biologist’s heart beating faster – the Arctic and the Antarctic, for one, or the wide stretches of the savanna in East Africa. These are some of the last large areas of wilderness that remain virtually untouched by human activity. And with his passion on the line, the head of behavioural research at Bielefeld University is always looking for – and finding – ways to travel to remote regions to study animals and ecosystems, and to inspire others to appreciate the beauty of nature and the importance of protecting the environment. Fancy a taste yourself?

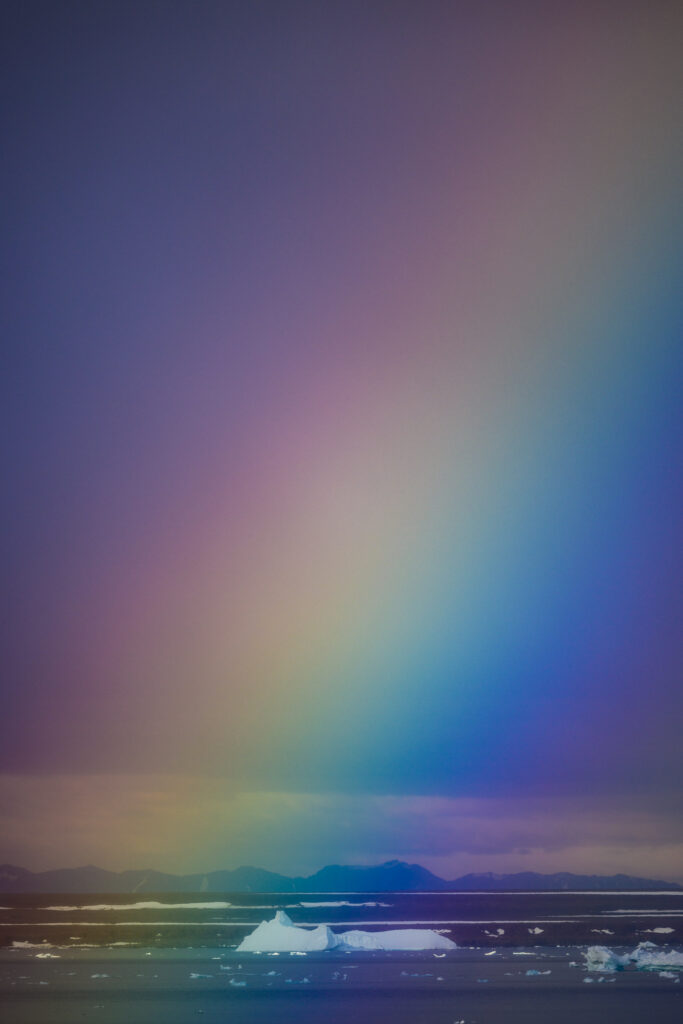

© Oliver Krüger

Oliver Krüger pulls out his tablet and clicks through a veritable trove of photos. He has taken thousands of impressive photographs during his travels over the past three decades, and some of these images are truly unique. ‘Here, an orca is hunting a humpback whale in the Antarctic. What a thing to behold,’ says Krüger, recalling the experience. Penguins and polar bears, a bar-tailed godwit in flight, or a sword-billed hummingbird: the 48-year-old researcher seeks to get as close as possible to wildlife and capture these ‘magical moments’ on film. One such magical moment was a sunset on Stonington Island in the Antarctic that he photographed six years ago, where a mighty iceberg rises up from the dark sea. ‘At times like these, everyone falls silent,’ says Krüger, still impressed today by the intense encounters with the natural world.

Bringing the polar regions to the people

After graduating from high school, Krüger’s first research internship in 1994 took him to Uganda. In East Africa, Krüger worked with gorillas and chimpanzees, photographed lions and leopards, and gained a wealth of experience. Other eye-opening experiences included two research trips in 1998 and 2000 to the Antarctic on the Polarstern, a German research vessel, where he worked for three months on each voyage as a research assistant. Since then, the icy wilds have continued to captivate his imagination. Almost every year, the biologist has traveled to the southern pole, not as a researcher, but as an expert who introduces others to the polar region on educational trips. He also undertakes these voyages in the hopes that people will be more willing to protect that which they know. ‘This unbelievable beauty, the sheer force of the elements colliding into you, and at the same time, the effective absence of humans does something to you. Anyone who experiences this comes back changed.’

Krüger, who grew up in Werther, considers himself ‘very fortunate’ that he can conduct his research all around the globe, but also on his home turf at Bielefeld University. One of his signature specialties is his work with birds of prey in East Westphalia, Germany. Some ten years ago, he also inherited a long-term study on the Galápagos Islands from his predecessor and doctoral supervisor Fritz Trillmich. ‘There is simply no other place on Earth where you can so clearly see evolution in action. The most amazing things happen there,’ enthuses Krüger, as he clicks the next photograph, showing a black marine iguana with a blood-red band on its mouth. Krüger explains that ‘these vegetarians have learned to dine on sea lion placenta. What an evolutionary step forward this is indeed, as placenta is much more nutritionally substantial than marine iguanas’ normal diet of algae.’

Richly rewarded for sacrificing the comforts of home

On the Galápagos, Krüger’s object of study is the sea lion. The research team from Bielefeld University works on the small, uninhabited island of Caamano. And the creature comforts of home? None to be found here. The requirements for working in the national park are strict. Researchers stay in simple tents, without showers or toilets. On the menu is mostly tinned food. For Krüger, living in such a pared-down way, far from the daily grind of emails and phone calls, is also ‘pure happiness,’ and the researchers are richly rewarded for doing away with the comforts of home. Mornings, for example, might start with getting woken up by a sea lion who has snuggled up next to the tent, snoring away. ‘They are not at all shy. We can study sea lions’ behaviour at close range without disturbing them. You can sit some five meters away from a female sea lion birthing a cub, and she doesn’t care in the least whether we’re there or not.’

Individuation as survival strategy

For Krüger, is the first step when it comes to researching the natural world is looking closely and observing. He is interested in how living things adapt to environmental changes. What is the evolution of behaviour? What individual differences exist? In Galápagos sea lions, the Bielefeld team was recently able to show that different foraging strategies can help mitigate the effects of climate change on the population. ‘Unfortunately, though, we don’t think that this will be enough,’ says the expert with concern. As the ocean gets warmer, some species will enjoy advantages due to their particular feeding behaviour, while others will suffer disadvantages for theirs. How will this change the makeup of the population? Can evolutionary processes react quickly enough to changes in the environment? How will individual animals be able to adapt? Such questions guide Krüger in his research, whether on sea lions in the Galápagos or on common buzzards in the Teutoburger forest.

This coming October, Krüger will once again head for the Pacific archipelago, and during the semester break beforehand, he will travel to the fjords in the northern reaches of Canada, towards Euraka, the northernmost weather station in the world. The biologist is looking forward to experiencing the wildlife of the north: ‘Last time, we saw polar foxes, musk ox, polar bears, and Arctic hares that don’t even lose their white fur because the summers are so short.’ So, is this work, vacation, or adventure? For Oliver Krüger, there is no distinction here to be made: every day is both work and play. And the trips that he takes in his free time pollinate his work at the university, broadening his horizons. As the researcher explains, ‘I’m able to make my lectures more compelling because I can speak about things that I have experienced firsthand.’ When he lectures on climate change in the Antarctic, he is not simply referring to dry, technical theory. ‘I have been there 25 times and I have seen with my own eyes – and documented in my photographs – how the glaciers are receding.’ Krüger fills his lectures with photos from his travels – another one of his trademarks. And so, on the next expedition, one thing is for sure: Krüger will have his camera ready at hand to preserve those astonishing encounters with the natural world.