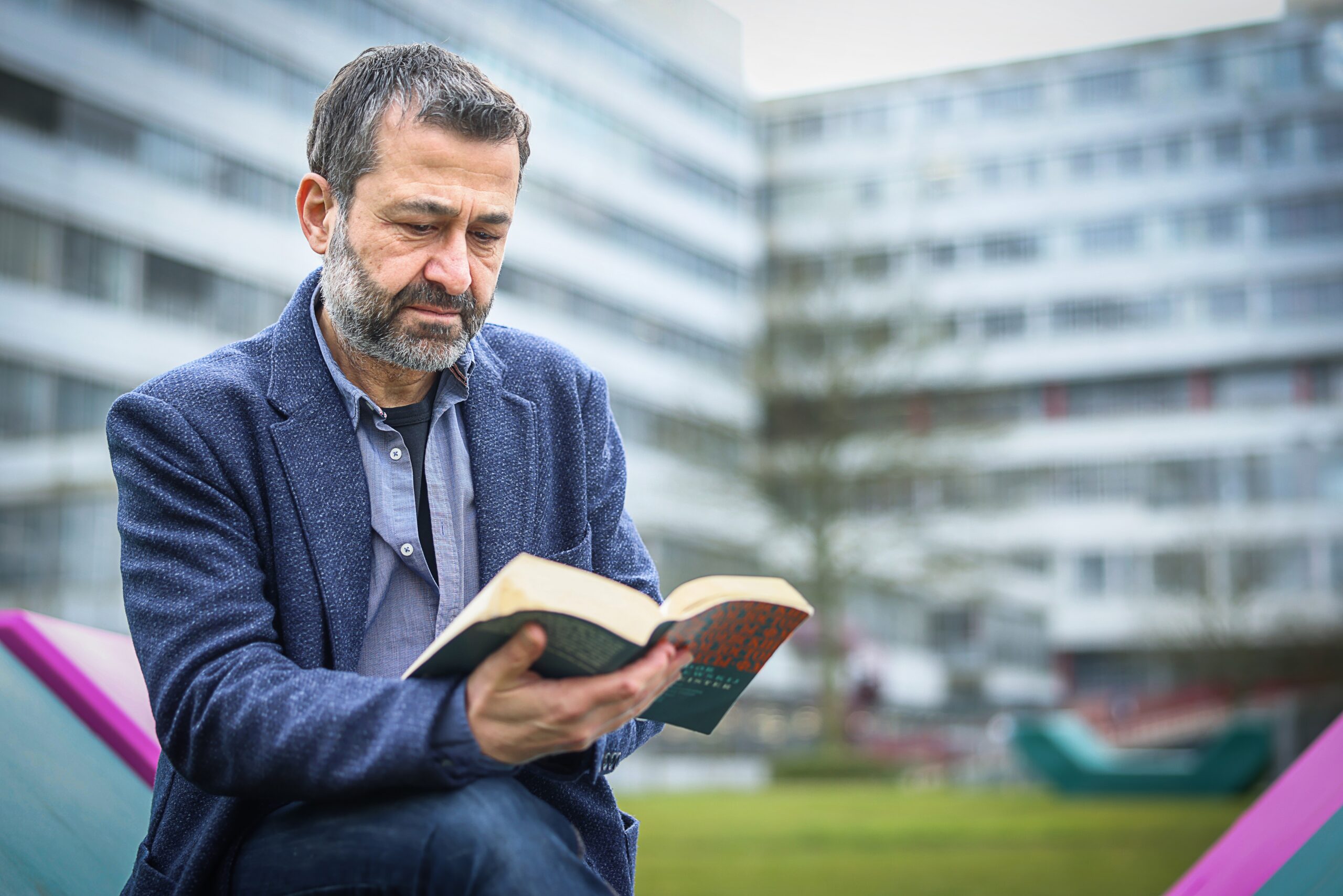

Dr Ekrem Düzen left his home country Turkey after losing his job as a member of the psychology department at the Izmir University. Having signed a peace petition urging the government to stop military operations causing civilian deaths in Kurdish-populated provinces, he lost all possibility of making a living in Turkey. The failed military coup d’etat attempt in 2016 gave the government in Turkey even more reason to persecute the intellectual elite and made his exit difficult, but Düzen managed it just in time. He is now living in Bielefeld where he is conducting the research study TransMIGZ on the Turkish community in Germany.

Journalist Amy Zayed spoke to him about the idea of the study and whether it had anything to do with his own story as a scholar at risk in his home country.

Amy Zayed: Dr Düzen, please explain to me what the actual research study is about?

Ekrem Düzen: It is about the Turkish migrant population living in Germany. There is lots of literature about migrants, mostly workers who migrated to Germany. It has a 60-year history! Our study is about social cohesion from a minority perspective. Usually, in literature social cohesion is understood or conceptualized from the majority perspective. But as time passes, European countries, and Germany being the first of them, are becoming more and more migrant countries. Our approach is no

t from a migration perspective, but from a transnational perspective. The home states of the migrants living in Germany these days are no far-away countries as they used to be. 40, 50 or 60 years ago, those countries used to be unreachable for them once they came to Germany. You had to travel for days and hours to get there, the means of communication were either not available, or not accessible to them. Even phone calls were difficult or expensive. In the era of transnationality travel is much easier, communication is much easier. It’s not just easier, it’s literally in everyone’s hands. Hearing your people’s voices or seeing them, communicating with them marks this era.

So that is one important issue that we look at. We’re trying to understand the transnational existence or presence of those migrant populations in Germany. And why do we focus on the Turkish minority in particular? Very easy: Because my fellow researchers and I are from Turkey. It’s basically the advantage of speaking the language technically.

Another reason is obviously that the Turkish minority is the largest migrant minority in Germany. Every 35th person in Germany has Turkish roots. If I tell you three per cent of the German population has Turkish roots, it kind of sounds little, but when I say, one in 35 people is Turkish it becomes clearer that it actually is quite a bit. So, we are going to do two things: The Turkish community’s existence in Germany is an in-between position. Sometimes they say we belong to Germany, sometimes they say we belong to Turkey, sometimes they say we belong to both and sometimes they say we belong to neither. Our aim is to try and reflect these people’s in-between position by their own perspective, with their own words. We’re going to do a participatory research, we’re trying to understand their positioning, their identity expression, their priority of belonging. And we’re doing that because the minority perspective is as important, if not even more important because majority usually sees minority as a threat to social cohesion.

It is quite interesting to find out how the minority perspective could contribute to social cohesion. And to show that there’s not much of a threat about it. And if there is, how to lessen it. Also, it is good to question subjects like: What is good about social cohesion? Should we have social cohesion? Is it a good target? Why can’t it be a peaceful co-existence? Are we going to make a German nation including all the minorities and migrants? Should everyone consider themselves German, or should everyone somehow keep their own identity?

Zayed: What I find interesting is the fact that when the first so-called guest workers came to Germany, unlike other European countries it took us ages to develop a system to include these people into the German society. These people came here, and had no easy opportunity to learn German, no opportunity to be with lots of German people as they were working most of the time. The idea behind that was that the German government thought for a long time these people would go back to their own countries. When they brought their families here, in many cases the first generation would say: We’ll go back next year, we’ll go back in five years, and then never ended up going back, and kind of started feeling an identity problem because obviously their children had started to include themselves into the German society. And identities started pushing especially at the 2nd and even 3rd generation at these people. People in Turkey, or even their own parents might say: You’re not Turkish enough, and their German peers might say: You’re not German enough. I’d find it so interesting to find out what this psychological difficulty, this social complexity has done to shape these people’s identities, or how they identify themselves, and also how these complex identity expressions influence social cohesion.

Düzen: What you say is very true. Especially the first generation was left to themselves. Even though they demanded language courses there were almost none available. And especially after the families came, they demanded language courses for women. And the German government didn’t see any need for that at that time. At some point, the German government realized that something had to be done about integrating these communities into German society.

Zayed: Which was sometime around 2004…

Düzen: Yes, it is unbelievable how they have waited so long! I mean, especially in the 70s and 80s Germany had some amazing opportunities to integrate the Turkish community into the German society, and at that time, Turkish people were absolutely willing to do so. But I have the impression that later all of a sudden the attitude of the German government changed, and it was like: You now have to learn German, you now have to speak German even in your own homes, which was kind of a crazy mindset after years of not even bothering for so long!

But then another thing happened: Since the current Turkish government came into power in 2002, there was a dramatic change in foreign politics in Turkey. In 2010, they started calling the Turkish communities abroad a diaspora. But diaspora was also a very negative word as it kind of implied you were talking about enemies or people that didn’t belong to your country. All of a sudden, the Turkish government hijacked that term diaspora to use it for their communities living abroad because they saw other countries using it for their own benefit.

It was a bit of a political maneuver, because by calling the Turkish community in Germany diaspora you could kind of diplomatically force the Germans to treat them nicely. And then they particularly addressed Turkish people in Germany telling them to live by the laws of their host country, but never really give their heart to any other country but Turkey. So obviously this strengthened this in-between position of Turkish people in Germany. It pushed at them even more, made their life more difficult.

And what we’re trying to do is to understand these people’s in-between position, torn between these two pushing social and political influences. In a way it is propaganda that is pulling at them from both sides.

Regardless of their generation, we call these migrants post-migrants. Because they are part of Germany in some way, they are not guest workers any more. We would like to establish that term in the literature.

The other thing is that the Turkish community in Germany is heterogeneous. We don’t call them Turkish people, but people of Turkey-origin. Because at least a third of them don’t call themselves Turkish. There are Kurdish people, there are Zazaki people, there are Alevite people. There are left-wing people, there are activists from all sides, there are civil society people … people from all social backgrounds. There are workers, there are teachers, doctors, politicians, so they exist in every social or cultural group. But the political image of Turkish people is: You are Turkish and you are Muslim. While actually this cliché says nothing about my definition of being Muslim, or who I really am. And we want to make a statement through this research that you have to approach this population not as a unitary population, but you have to take into account the heterogeneity and fragmentation of this population. Because there are certain images or clichés in the minds of German as well as Turkish politicians. In Turkey it’s the conservative, religious, valuable Turkish person who belongs to Turkey, and in Germany it’s the well-integrated citizen who speaks German even at home. But the Turkish population is neither of these images. They have their own style and we want to understand how they developed it and how they express it. What are their identity expressions, not necessarily their identities.

Our idea is to tell both sides: Get over your old outdated clichés and images in your minds and stop throwing them at these people, just let them be who they are. Listen to these minority perspectives! Here’s your data! Because there won’t be proper social cohesion if you don’t listen to these people’s perspectives. So that’s kind of our target.

Zayed: How fare have you come in your study?

Düzen: We’ve been doing the research for a year, and we still have another 18 months to go. We’ve completed a two-step media study. First, we did a general screening, just collected everything we had encountered. After this initial screening, we properly sampled the media that is mostly consumed by Turkish post-migrants. But the aim was not to understand their media consumption habits, we wanted to understand how Turkey or the Turkish government addresses them, and on the other hand how Germany addresses them.

We are now analyzing the image of the post-migrant in the mindset of the Turkish government, and on the other hand the image in the German mindset. To show that one wishes them to integrate, while the other wants them to stay loyal to Turkey.

The second part is an archive study. Because until the whole diaspora policy was launched in 2010, no matter which government Turkey had, the attitude towards the Turkish population in Germany was very much similar. But the present government specifically focused on them to be loyal to Turkey. The present government follows the same attitude even in their domestic politics, basically by consolidating those who are with them, and disregarding those who are against them, and by that they basically split the whole Turkish society.

Zayed: Where did the idea for this research come from? Especially as you’re not a migrant researcher, but a trained psychologist with at least 20 years’ experience as a psychotherapist.

Düzen: At the beginning I was only supposed to be a consultant. But one of the main team members at the time had to leave the project. So, I jumped in. I was probably the most available at the time. I have a lot of experience working with parents and child development. I also worked for UNICEF. I developed training programmes and documents and research. And later I got involved in youth studies and youth mobilization. And just before I came to Germany I was involved in youth mobility in the Balkan countries as well. So, the idea of transnationalism was already in my head, although it was obviously from the young people’s perspective. That is how I ended up with this project.

Zayed: Was the project already in the making when you came, or did it start when you were here? And is it in any way linked to you personally as a displaced scholar making your own journey in transnationalism now?

Düzen: No, the project started in my third year in Germany. But let me start from the beginning: In January 2016, there was a peace petition which I signed. And those who signed the petition were dismissed and interrogated by the government. I was the second in the whole country who got dismissed of my position as a scientist because of that signature. And then obviously the failed coup happened in July, and the government took advantage of that and dismissed more academics. And hundreds of academics found themselves in Germany, and I am one of them.

Zayed: But why Bielefeld? Everyone wants to come to Cologne or Berlin, why Bielefeld?

Düzen: Because of my mentor. My connection was the director of the IKG. I did not know him personally before, but one of my colleagues referred me to Andreas Zick. And without further ado, he told me to immediately get my backsides out of Turkey and come here. It took me half an hour to make that decision. I was lucky in a sense to arrive in Bielefeld. My mentor is a guy who sticks to his word and defended our position from the beginning until now and I am very certain until the end. And then I became the connection for other academics who needed a hand. This is probably the greatest part of the story. We have this great opportunity here to do a good job which our country denied us, and so let’s do it really well.