The Bielefeld behavioral scientist Professor Dr. Joseph Hoffman was involved in a large-scale study with data on Antarctic fur seals. In a comparative analysis of pedigree-based mutation rates, far-reaching insights into the evolution of mutations in vertebrates could be gained. Individualization enables animal species to better adapt to their environment, which is changing due to climate change, for example. Mutations can also play a role in this. In the interview, Professor Hoffman explains which animals were studied, why knowledge of germline mutation rates is so relevant, and why the time between generations is a factor that should not be underestimated regarding hereditary diseases.

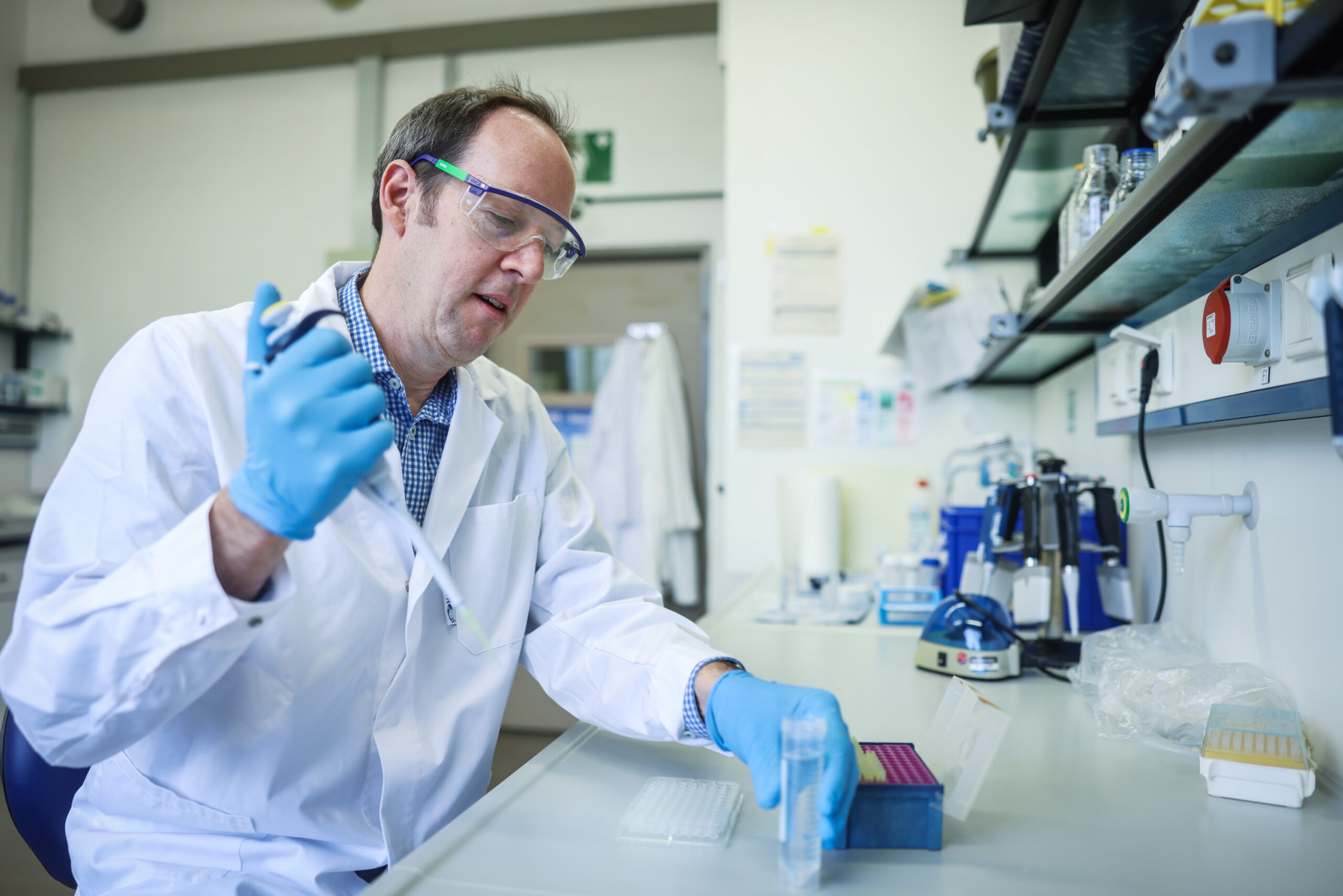

Professor Hoffman, you were recently involved in a large-scale study looking at germline mutation rates in vertebrates. What was being investigated?

Professor Dr. Joseph Hoffman: A germline mutation is a change that has occurred in the egg or sperm of a parent. If it is passed on to the child, it is often possible to trace back whether the mutation originates from the father or the mother. With an interdisciplinary team, we looked at how the rate of these germline mutations differs between different vertebrates.

©

Which animals were studied?

A total of 68 vertebrate species were examined for the study, including mammals, fish, birds and different reptile species. Some of the animals were from the wild, but many also came from zoos and conservation projects. We always must examine trios, thus mother, father and the offspring. This is often difficult in the wild.

Why is it important to know more about germline mutation rates?

Mutations can be an important factor in the conservation of a species. Some mutations are neutral, some have positive effects, but many also have negative effects and can cause diseases. That’s why it can be crucial to find out more about how often and when mutations typically occur. For example, we now know that in the many species, most mutations originate from the fathers. This may be important for humans as well. In recent years, there has been some research on the fact that older fathers often pass on more mutations and, in this respect, the risk of diseases in the offspring could also increase with the age of the fathers.

What were the results of the study?

We found large differences in mutation rates between species. Above all, the generation time, which is the time interval between the individual generations, together with other life-history characteristics such as fertility and age at sexual maturity, plays a major role and explains the differences between the species. In addition, mutation rates also depend on the long-term size of a population. They are lower in common species. Domestic animals, in turn, tend to have higher mutation rates than wild animals.

What specifically was your contribution to the study as a professor at Bielefeld University and as a member of the British Antarctic Survey?

I contributed data on the genomes of Antarctic fur seals. This is a fur seal species that occurs almost exclusively in South Georgia, a group of islands in Antarctica. We have been taking samples of the animals there for decades, and our dataset now includes about 15,000 individuals spanning several decades. From this, I have selected several parent-child trios.

You are also working in the collaborative research center Transregio 212, which deals with ecological niches. You are also involved in the interdisciplinary follow-up project Jice of the universities of Bielefeld and Münster. This is about individualization in a changing environment. Do you see any connection between this and the study?

In the study, we examined the mutation rates of certain species and not specifically of individuals. Nevertheless, I do see certain connections in terms of evolutionary rates and mutations. The environment, in which Antarctic fur seals live, is changing rapidly due to climate change. Therefore, the pressure on the animals to adapt to the new conditions is increasing, and mutations may play a role in this. The population of fur seals in South Georgia has declined by 40 percent since the 1980s. Using the genomes, we could see that the worsening environmental conditions have led to an increased selection against inbreeds, which often have more deleterious mutations. Currently, we are developing a follow-up project to study mutations at the individual level. We want to follow individual fur seals throughout their lives to quantify how mutations accumulate over time depending on sex, age, genetic factors and environmental factors.

You are currently focusing on epigenetic aspects. To put it simply you examine the extent to which the environmental conditions of the fur seals play a role in determining which genes are switched on and which are not. What exactly is this about?

We know that the environment affects how genes are read. In some cases, these changes even seem to be passed on from one generation to the next. We now know this in humans as well. There is evidence, for example, that traumatic experiences can still show up in the genome over generations. We assume that epigenetic changes in animals have an influence on selection and adaptation to niches. For this purpose, we compare pups of sea bears born under favorable and unfavorable environmental conditions.